The goddess Kali is everywhere in Puri, portrayed in some of the fiercest, wildest, most bloodthirsty forms I have seen in our travels around India. A string of human skulls around the neck is nothing – Odishan Kalis have blood dripping from their mouths, they plunge lances into the chests of the humans below their feet, their eyes are crazed with lust for yet more blood.

The goddess Kali is everywhere in Puri, portrayed in some of the fiercest, wildest, most bloodthirsty forms I have seen in our travels around India. A string of human skulls around the neck is nothing – Odishan Kalis have blood dripping from their mouths, they plunge lances into the chests of the humans below their feet, their eyes are crazed with lust for yet more blood.

Kali is the goddess of the graveyard. She rules the burning ground, the ultimate place of transformation where the body of this earthly life is promptly dispatched, the soul freed for the next stage of its journey.

Today in Puri I saw, right up close – and for the first time in all my travels through India – the details of a body being burned.

The morning started out (as it nearly always does) with a walk. Alan and I decided to visit the more touristy beach in Puri. It’s south of the beach we’re staying close to, which is certainly popular but not nearly as populated as the touristy beach. The touristy beach is located closer to the Jagganath temple, the central focus of Puri, and is also where many hotels and handloom shops are located. The two beaches are separated by a wide creek of wastewater and sewage running into the sea that we don’t dare to cross, so we walked on roads until we reached the access road to the touristy beach.

It was already past 10:00 by the time we got there, and the beach was full of happy families playing in the water, jumping into the long waves, splashing each other and taking selfies. Many people lounged under hired beach umbrellas, vendors stopping to offer beautiful conch shells or dubious pearls for sale. Colorfully caparisoned camels paraded up and down the beach, occasionally carrying tourists who’d actually paid for a ride. (I myself would never dare – those camels are really huge.)

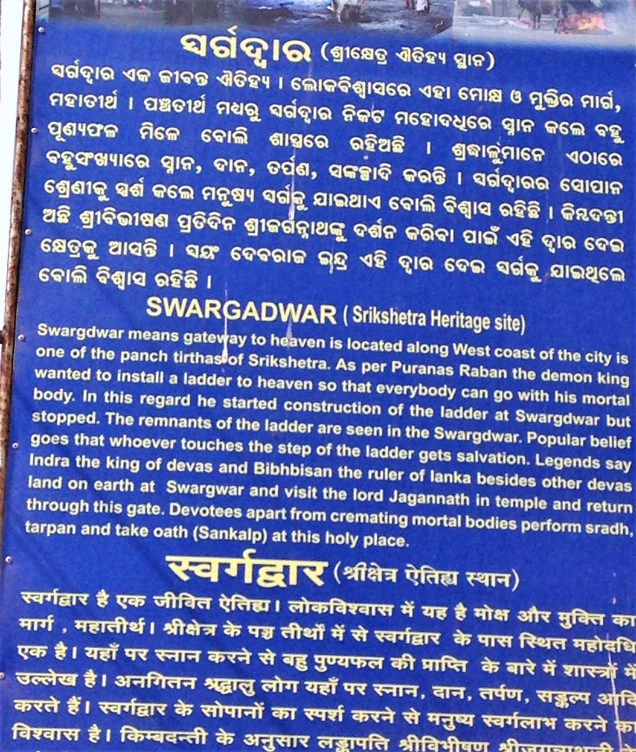

The sun was strong, so after a while we turned away from the sea and towards Marine Road running alongside the sea front, and the line of tea and snack sellers by its side. We drank small cups of overly sweet tea, then turned up toward the Swargadwar, or “gateway to heaven,” indicated by one of the helpful blue signs you find all over Puri. These signs educate you in three languages – Oriya, English and Hindi – about many of the religious locations around town. I did not realize at that moment, however, that “swargadwar” is the term for a burning ground.

We passed into a small temple dedicated to Kali. On every surface and pillar was a different depiction of her in the most fierce, bloodthirsty guises. I kept stopping and looking at her as we slowly made our way to a short flight of stairs. “We’re at the burning ground,” Alan said.

As we emerged from the temple, I saw an empty square of earth to our left. It wasn’t large, perhaps 80 feet by 80 feet. The earth was not brown or red, but ashy white and gray. Thick smoke billowed out from piles of logs, just feet from where I stood.

We moved to the side of the burning ground that faces the sea, and joined the groups of silent people standing and watching. Others sat on stone benches provided for the purpose. I surveyed the ground in front of us. There were several fires in progress, and men in t-shirts and cotton lungis, their feet bare, walked back and forth across the ground, tending the fires. One pile of logs was nearly consumed, just at the point where the structure of the entire fire is ready to collapse into a heap of embers. Another was flaming more fiercely, and as I watched, one of the men lifted a blue blanket with a long stick, and laid it across one end of the fire.

Then I looked at the pile closest to where we stood, and experienced a small jolt of recognition: I was looking at a human skull. The flesh had all been burnt away, and the shape of the upside-down skull was clearly visible, its blackened-greasy surface shining through the thin orange flames.

There was a bustle of activity at the right side of the square. About a dozen people were assembling at the side of the burning ground, and several more men clustered around a litter on the ground. There was a body on the litter, and as the men unwrapped it, I saw her: a woman who appeared to be in late middle age. Her forearms, hands and feet looked like anyone else’s, with red and gold bangles on her wrists. Her hair, parted in the middle, had the pinkish color of white hair that has been hennaed and then faded out. She wore a blue and white sari, its pattern visible over her huge stomach, as round and distended as if she were in advanced pregnancy. I wondered if she had died of a stomach cancer, if what I was seeing was the result of a tumor or some other disease state. Or maybe she was just like any of the older ladies I see on the streets of India, with their dyed hair, nice saris and jewelry, bulky figures and air of authority.

The men lifted the lady’s body, and stooping over, walked around the waiting pile of logs several times. They stumbled over some random chunks of burnt log, until one of the workmen pulled them away with a stick. Their circuits complete, the men laid the lady on the pyre of logs and stepped back.

Now the professionals stepped in, laying logs beside the lady’s body, and in a V-shape at her head. One arm kept flopping down and getting in the way of the men’s work, so one of the men who’d carried the lady’s body finally picked her arm up by the wrist and held it on top of her high-curved stomach until the logs were place. Then he released the arm and it flopped down. I noticed the gold-colored bangles and wondered if they were really gold, or just gold-colored glass. It was hard for me to imagine the family would burn gold jewelry with their relative’s body.

Now it went quickly. A man stuffed dried brush at the base of the pile, right beneath the lady’s head, and lit it. Men poured some liquid on the fire near the lady’s head, and it flared up. Next they brought something yellow in plastic pouches – ghee, perhaps, I thought – and squeezed it out onto the fire. This set the flames leaping, and then two bare-chested priests circled the fire, casting white powder onto it.

About a dozen people stood close by through these proceedings, hands folded, watching the entire process. Everyone looked solemn and serious, but I saw no one crying, nor, now that I think of it, anyone wearing white. Everyone but the priests wore ordinary clothes.

Presently the laypeople began to come forward – the family members, I imagined – each adding a small white log to the fire at the lady’s head. I supposed the small logs were sandalwood. As the flames grew thicker and redder, everyone stood back, continuing to watch. Now one of the burning-ground men came near, and using a long stick, stuffed a bundle of pretty pink fabric into the fire near the lady’s feet. I wondered if it was one of her favorite saris. Then another brought a dark-red blanket and used a stick to lay it across the lower part of the fire. Some of her personal possessions being burnt with her? Was this the blanket she’d been wrapped in, being hygienically burnt with her body? I don’t know, and there was no one to ask.

We lingered a little longer as the flames obscured the lady’s body. I watched the burning-ground men poke at some of the other fires with long sticks, moving pieces of unconsumed wood to nearby fires. I wondered how long it takes to burn a body completely – two hours? Three hours? Again, there was no one to ask. Everyone around us was silent and absorbed.

I looked up past the burning ground to the beach beyond, to the sun shining on the sea, and silhouetted in its stark light, the figures of people splashing in the waves and playing on the sand.

One final look at the lady’s pyre. It was burning fiercely now, the entire pile encased in flame. I could see no more sign of her, neither of what she had been nor what she was becoming.

We turned to exit the burning ground, but our way was blocked by a group of people carrying a body on a litter into the ground. We went out another way, and heard drumbeats to our right, overwhelmingly loud. A group of men carrying yet another body covered in marigolds was heading up the hill towards us, a few men and women trailing behind. We turned in the other direction towards the Jagganath temple, and as we walked on, were gradually enveloped by the sounds, scents and sights of the temple markets. It was just another day.

Note: I took no photos of the burning ground. It did not feel respectful to me to do so. If you want to see what the burning ground is like, you can find videos on YouTube. Just search for “swargadwar” and you will find what you are looking for.

Such great description, Aliza. It brings me back to traveling in India more than 20 years ago. Such an interesting country.

LikeLike

Hello Susannah! So good to see you here! And thanks for both reading and commenting. India has certainly changed in many ways over the decades — I can’t believe it’s been almost 40 years since I arrived for the first time — but it is still India.

LikeLike

Really interesting post Aliza, I had part of a plan to go the burning ground, but didn’t get there in the end. How did it make you feel? Was it upsetting, or more absorbing? I expected I would feel rather disturbed by it, having not seen anything like that before, but perhaps not?

LikeLike

Hi Kate! I didn’t find it upsetting, but it definitely disturbed the assumption my mind usually makes that death is remote from me. Death is so very present in India, and the burning ground was one more instance of that. The fact that the lady’s arm was so limp, as if she were asleep or unconscious instead of dead, the way the man picked her arm up by the wrist and held it on her belly out of the way for the log to be placed….and then just a few minutes later, her skull was as blackened as the skull I saw on a pyre shortly after we first arrived. So immediate. So yes, that is disturbing in the sense that it disturbs the status quo. I felt the tenderness of life, the fragility of the body’s existence, the suddenness with which someone is gone when they’re gone.

LikeLiked by 1 person

And life goes on. Interesting post.

LikeLike

Thank you, Sidran. I take it as a real compliment, coming from such a thoughtful writer as you.

LikeLike

Thank you, Sidran. I take it as a real compliment, coming from such a thoughtful writer as you.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The pleasure was all mine, Aliza.

LikeLike